28 March, 2010

Curator's Notes

The curators and archivists at the Victorian Mechanical Museum have departed on their annual spring sabbatical and hence, we must take a similar break here at the Hawkins Strongbox online exhibition. We will return to our normal exhibition schedule in mid-April.

Among our upcoming exhibitions: materials relating to the Kansas City-based Vanderzee Detective Bureau; documents pertaining to the mysterious and notorious Dr. Enoch Cyncad; and an actual æther firearm preserved within the strongbox itself.

As always, thank you for visiting and for your continued encouragement and support.

Among our upcoming exhibitions: materials relating to the Kansas City-based Vanderzee Detective Bureau; documents pertaining to the mysterious and notorious Dr. Enoch Cyncad; and an actual æther firearm preserved within the strongbox itself.

As always, thank you for visiting and for your continued encouragement and support.

Exhibit Subjects:

Curator's Notes

21 March, 2010

Item 107: The 1939 World's Fair Postcard

Collection Item 107: The 1939 World's Fair Postcard. 1939.

Item 107 is a small, but still very significant item. In July of 1939, Timothy Deakin, a few months past his 84th birthday, attended the the New York World's Fair and subsequently mailed a postcard to a friend then living in Munhall, Pennsylvania. It is the second item we have exhibited that dates from the 20th century.

The postcard was sent to G. Thomas at 3975 Main Street in Munhall, a small borough just outside of Pittsburgh. The message on the card reads:

So wonderful to see you despite such a brief visit. James and Min have brought us to the fair. The world of Tomorrow feels just a bit like yesteryear to us. Berkley would have no doubt found Elektro the Robot quite amusing, God rest his soul.

We regret we will not see you again as we will catch a plane in New York City.

All our best. T.

According to Deakin family records, Timothy Deakin was residing with his son Everett in southern California in 1939. His grandson James lived in western Pennsylvania with his wife Minnie and their four children. It can be assumed that Timothy had taken an extended trip to Pennsylvania during the early summer of 1939, and visited not just with his family but also with the mysterious G. Thomas. James and Min later escorted Timothy to the World's Fair just outside of New York City, after which it appears he boarded an airplane and returned to California.

Was G. Thomas in fact Geoffrey Hawkins, who had vanished from society some 28 years earlier in 1911? The tone of familiarity and the sentimental reference to Berkley Vanderzee, both contained within the missive, could certainly be clues to that effect.

Exhibit Subjects:

Collection Item,

Geoffrey Hawkins,

Timothy Deakin

15 March, 2010

Item 20: The Æther Collectors: Matthew and James Hardy

Matthew and James Hardy dressed for æther collection. 1875.

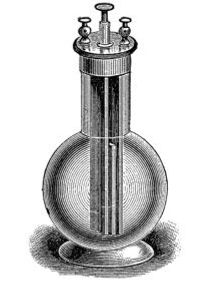

Sons of a wealthy western Pennsylvania glasswork tycoon, Matthew and James Hardy took leave of their father's business in 1870 and went on to make one of the most important, albeit largely unrecognized discoveries of the 19th century. During the summer of 1874, while exploring catacombs and caverns deep below the surface streets of London, the two self-proclaimed adventurers and explorers stumbled upon a plasma-type gas that would ultimately be dubbed æther upon later examination by Berkley Vanderzee and Geoffrey Hawkins. An 1875 photograph of Matthew and James Hardy has been cataloged as Collection Item 20.

A patient, generous and indulgent father, Jasper Hardy wished his two sons well when they set out to see the world in the spring of 1870. Their wanderings brought them to London in early 1874, where rumors of vast networks of tunnels and caverns below the city surface piqued their interests. While preparing for their initial subterranean expedition, they met Berkley Vanderzee, from whom they acquired various supplies and mechanical instruments deemed necessary for their forthcoming journeys. Vanderzee in turn brought their plans to the attention of his friend Geoffrey Hawkins, who was intrigued enough to underwrite some of their costs and expenditures. It was on their second expedition in late August of 1874 that they made their momentous discovery. The brothers subsequently presented samples to Vanderzee and Hawkins, who named the gaseous matter æther. They took the name from Greek mythology, æther being known in that context as the substance of the heavens. Within twelve months, Vanderzee and Hawkins had developed the first functioning æther power cell.

The æther deposits that the brothers discovered were deep underground and typically engulfed in toxic gases. Successful extractions depended on the two being outfitted with specialized optics and breathing filters, thus accounting for their appearance in the above image. The Victorian Mechanical Museum displays a number of æther-collection items at their London location, including the optics and masks that Matthew and James are wearing in the photo.

From the collection of the Victorian Mechanical Museum.

Matthew Hardy chronicled his subterranean adventures in a book entitled My Travels Underground, published in London in 1889, but he and James never revealed publicly any information about æther or the æther-powered weapons and devices subsequently created by Vanderzee and Hawkins, and later Timothy Deakin and Falynne Hyperion.

Exhibit Subjects:

Ætherdynamics,

Berkley Vanderzee,

Collection Item,

Geoffrey Hawkins,

James Hardy,

Jasper Hardy,

Matthew Hardy,

Victorian Mechanical Museum

09 March, 2010

Item: 111: The Adler Fanshaw Envelope

Collection Item 111: The Adler Fanshaw Envelope and Contents. 1953.

The contents are:

- a cabinet card photograph of Adler Fanshaw, dated 1893. (Item 111A)

- a newspaper clipping of an obituary for Fanshaw, annotated with a date of August 15, 1953. (Item 111B)

- a copy of Startling Stories magazine from July 1949. (Item 111C)

- an incomplete transcript of an apparent interrogation of Fanshaw, date-stamped October 5, 1953. (Item 111D)

(Select each page for an enlarged image. A separate transcription of all four pages can be found here. )

Page 1 (Document Page 2)

Page 2 (Document Page 3)

Page 3 (Document Page 4)

Page 4 (Document Page 5)

The Fanshaw document is quite a discovery, albeit a very enigmatic one. It is incomplete; page one is missing and it is unknown how many pages followed page five. It is an original typed document, not a carbon copy. It is likely that it was transcribed from another copy at the time of the OCT 5 1953 date stamp, and that occurred some seven weeks after Fanshaw's death on August 15. The four pages appear to then have been removed or stolen at some point from their place of storage.

Who was interrogating Adler Fanshaw? Archer Bowens notes, "The recipient of the pages made an intriguing notation--connecting the initials "CS" with the name Starkweather. This proved to be a fortuitous clue as it directed us to the person of Cameron Starkweather, information about whom existed in our own archives here at the Victorian Mechanical Museum."

According to internal records, Victorian Mechanical Museum Curator Robert Fitzhugh was visited on December 2, 1947 by a gentleman who identified himself as Jonathan Rogers, an American private investigator working at the behest of a lawyer settling estate issues relating to a member of the Hawkins family. He was searching for any documents and personal effects that may have belonged to Geoffrey Hawkins, who had disappeared in 1911. Suspicious of the man's story and motives, Fitzhugh dismissed him politely but firmly. Fitzhugh, a retired British intelligence officer, immediately began an investigation of the man.

After making a number of discreet inquiries to former associates in the intelligence community, Fitzhugh discovered that Jonathan Rogers was in fact Colonel Cameron Starkweather, an American military intelligence officer. It was determined that Starkweather was at that time assigned to Project Nick, a top secret operation located at Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. Project Nick was created to determine the feasibility of particle beam weapons, applying theories developed by the late Nikola Tesla. It immediately became apparent why Starkweather was pursuing information and materials relating to Geoffrey Hawkins; the members of the Society of the Mechanical Sun had invented particle beam weapons using ætherdynamic science some six decades earlier.

Project Nick was supposedly disbanded a few years after its inception, so it is not clear why Starkweather was so aggressively pursuing the matter with Fanshaw in 1953. A similar initiative was undertaken in 1958 by ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency; later DARPA) and given the codename Project Seesaw. It is unknown whether Starkweather had any involvement with that operation.

Apparently, a frustrated Starkweather learned very little from any of his investigations. The recipient of the four-page transcript even made a point of underscoring one particular statement made by Starkweather: " . . .we have to date been unable to collect any substantial information or resources concerning Mr. Hawkins and his associates."

It is not known exactly when Starkweather conducted the interview with Fanshaw, but it would have occurred sometime between October 10, 1952 and Fanshaw's death on August 15, 1953, based on Fanshaw's stated age.

Presented next is the newspaper clipping of Fanshaw's obituary:

The annotated date of August 15, 1953 refers to the day of Fanshaw's death; that is confirmed by the Saturday reference in the obituary. The date of publication was either August 16 or 17; Fanshaw's funeral was held on August 18, 1953. Though unidentified, the newspaper was likely the Homestead Daily Messenger. Fanshaw's home in Munhall, Pennsylvania was quite close to the Duquense location where the Hawkins Strongbox was discovered in 2003.

Also included in the envelope was a copy of the magazine Startling Stories that was referenced in the interrogation transcript.

The short story, The Battle Below, is listed on the contents page with the tag line, "Deep below the streets of London, secrets await discovery." Archer Bowens recalls, "The Musuem's last contact with Adler Fanshaw was in the early 1940s. He had donated a number of notes and records relating to his tenure at the London Evening Gazette during the 1880s. He had published a few obscure mystery novels in the '30s and a smattering of magazine stories during the war. The Battle Below was an unusual departure for him, coming so late in his life and referencing long kept Society secrets. One can not help but question his motivations for writing and publishing it."

The remaining item found within the Fanshaw Envelope is somewhat of an anomaly, but significant nonetheless. This cabinet card portrait of Fanshaw is dated 1893, predating the other items by sixty years.

In the portrait, Fanshaw wears a Mechanical Sun brooch on his lapel. His membership in the Society of the Mechanical Sun had been long suspected but never confirmed. It would appear that question has now been resolved.

Exhibit Subjects:

Adler Fanshaw,

Ætherdynamics,

Cabinet Card,

Cameron Starkweather,

Collection Item,

Geoffrey Hawkins,

Victorian Mechanical Museum

06 March, 2010

Item 49: Falynne Hyperion Cabinet Card

Item 49: Cabinet Card of Falynne Hyperion. Early 1882.

We have to this point said little of Falynne Hyperion, an original member of the Society of the Mechanical Sun, whose 1882 cabinet card portrait we now reveal. We have previously exhibited the portraits of the other founding members, Geoffrey Hawkins (Item 46), Timothy Deakin (Item 47) and Berkley Vanderzee (Item 48). The cabinet card of Falynne Hyperion is classified as Collection Item 49.

Falynne Jane Maddock was born to parents Magnus and Ivory Maddock in Paris in on 15 May, 1853. Magnus Maddock, a professional magician, was better known to the general public as Magnus Hyperion. Maddock was born and raised in London, but shortly after his marriage to Ivory in 1848, he traveled to Paris to study under the tutelage of master conjurer and performer Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin. The couple returned to London in 1857 where Magnus, as the Grande Hyperion, became one of England's premiere stage magicians.

Ivory Maddock was brutally murdered in October of 1862, leaving Maddock as the sole caregiver for the young Falynne. She soon became immersed in her father's professional life and was especially fascinated with the mechanics of the illusions he created and performed. By age seventeen, she was designing and building her own illusions that Magnus happily included in his repertoire. She traveled extensively with her father throughout much of Europe and the Americas prior to his retirement in 1875. When her father's tour stopped in Chicago during the summer of 1873, she met cattle rancher Nicholas Vanderzee. Impressed with the young woman's intellect and natural abilities, Nicholas suggested she contact his brother Berkley, a well-known London inventor and watchmaker. Nicholas would write his brother on Falynne's behalf and suggest an informal apprenticeship to commence when Falynne returned to London later that year.

Falynne had little interest in theater and celebrity, and with the help of Berkley Vanderzee, instead channeled her passion for mechanical design into successful enterprises as both inventor and entrepreneur, remarkable achievements in the male-dominated society of Victorian England.

As a tribute to her father upon his passing in 1878, she formally adopted Hyperion as her surname.

The set of four cabinet cards and the Hawkins timepiece have been formally categorized as Lot 1: January 1882.

03 March, 2010

Correspondence: George Eastman and Timothy Deakin

As always, our thanks to all our exhibition visitors who have contacted us with kind words and encouragement. We truly appreciate your time and attention.

In 1886, Timothy Deakin traveled to Rochester, New York at the request of George Eastman. Though their discussions were closely guarded and largely undocumented, it is believed that Deakin provided Eastman with numerous optical designs that Eastman in turn incorporated into his own Kodak line of cameras, the first of which was introduced in 1888. In exchange, Deakin became a shareowner of the Eastman Dry Plate and Film Company (soon to become the Eastman Kodak Company), a shrewd business maneuver that kept him financially secure for the remainder of his life. He especially profited when Eastman completed a controversial refinancing of the company in London in 1898. Another distinct benefit of his close relationship with Eastman was access to prototype cameras and film processes, long before such products reached the general public. Deakin quietly assisted Eastman when the company opened offices and a retail space on Oxford Street in London in 1888. He was also granted access to the processing laboratory at the Oxford Street location where he was able to conduct his own occasional photographic research and experimentation.

- Andrew T. asks: "You note that Timothy Deakin was a photographer by trade, but also characterize him as a scientist, inventor and mechanical genius. Was he known for any important innovations in photography?"

In 1886, Timothy Deakin traveled to Rochester, New York at the request of George Eastman. Though their discussions were closely guarded and largely undocumented, it is believed that Deakin provided Eastman with numerous optical designs that Eastman in turn incorporated into his own Kodak line of cameras, the first of which was introduced in 1888. In exchange, Deakin became a shareowner of the Eastman Dry Plate and Film Company (soon to become the Eastman Kodak Company), a shrewd business maneuver that kept him financially secure for the remainder of his life. He especially profited when Eastman completed a controversial refinancing of the company in London in 1898. Another distinct benefit of his close relationship with Eastman was access to prototype cameras and film processes, long before such products reached the general public. Deakin quietly assisted Eastman when the company opened offices and a retail space on Oxford Street in London in 1888. He was also granted access to the processing laboratory at the Oxford Street location where he was able to conduct his own occasional photographic research and experimentation.

Photograph:Timothy Deakin standing in front of the Eastman Kodak London offices,following relocation from Oxford Street to Clerkenwell Road. 1902.Courtesy of the Deakin Family Archives.

Exhibit Subjects:

Correspondences,

Deakin Bro's Photography Studio,

George Eastman,

Timothy Deakin

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)