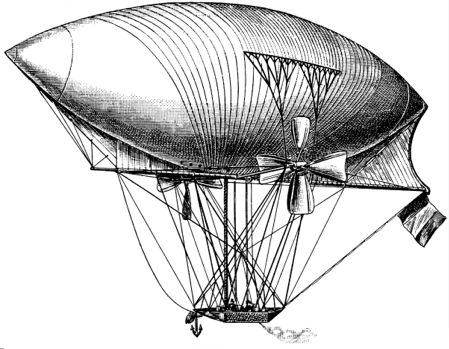

Item 78: Patent Diagram for the Hawkins Steam Coach. 1888.

The Hawkins Steam Coach appears to have been both a tremendous success and bitter disappointment for Geoffrey Hawkins. It was one of the first major industrial design projects completed by his then fledgling Hawkins Industrial Laboratory. Three prototypes were produced from 1888 into early 1889. However, beyond this patent diagram that was found in the strongbox, little to no physical evidence remains of Hawkins' early attempt at building a horseless carriage. Most records associated with the project were likely destroyed in the catastrophic fire the that consumed Hawkins' lab in 1896.

In a letter dated June 17, 1886 (HS Item 317), Hawkins' American friend Chester Alexander made the following query of his British contemporary:

" . . . and so then, what is the status of your intriguing carriage project? Your last correspondence indicated that you were in deep study of Rickett's earlier designs and that you had even managed to examine the vehicle he had built for the Earl of Caithness."

Alexander was referring to Thomas Rickett, a Buckingham inventor who had designed a steam carriage some three decades earlier.

The fall 1888 issue of Hawkins Journal of Advanced Science and Industry included a very brief article noting that production had commenced on a prototype. It was accompanied by a spot illustration that essentially matched the patent diagram. According to a note from Hawkins to his accountant in December of 1888, his first steam coach met with "sabotage most foul" sometime in November of that year, though he surprisingly provided no other details.

Two additional vehicles were reportedly manufactured by the end of 1888, but indications are that Hawkins kept them under tight guard. In a letter to her mother, Lady Constance Ockley noted that Hawkins had revealed " . . . a marvelous horseless carriage" to guests on Christmas day at his country home in Faversham. But she also mentioned that her host had employed "brutish gentlemen in leather topcoats armed with unusual pistols" to guard it around the clock.*

In January of 1889, accounting records indicated that Hawkins was preparing to purchase a vacant factory building near Faversham, but backed out of the arrangement at the last minute. Again, a note from Hawkins to his accountant provided clues to the fate of his steam coaches. "They have managed to infiltrate my defenses and the second is now gone as well," he wrote in a letter dated January 17, 1889. "I am securing the remaining vehicle beyond their reach. It is indeed sad that society will be denied this amazing and beneficial boon to science and industry, due to the jealousy and greed of my rivals. They have suppressed a wonderful invention, but I have neither the will nor determination to battle their attacks at this time and I can no longer continue to compromise the safety of those in my employ."

Who are these unnamed rivals that Hawkins refers to? German automobile inventors Karl Benz, Wilhelm Maybach and Gottleib Daimler were equally busy during the same decade pioneering their own horseless carriages. Were any or all of these individuals somehow threatened by the technologies and innovations contained within the Hawkins Steam Coach? Enough to employ the "sabotage most foul" that Hawkins alluded to?

And what of the third and final Steam Coach that Hawkins secured beyond the reach of his unnamed enemies? Does it still exist, perchance collecting dust in some remote location beyond the reach of historians and mechanical scholars? Let us hope that the answers may lie deeper within the strongbox we continue to explore.