|

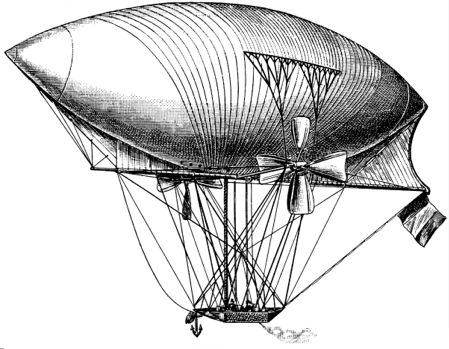

| Tintype of Noah Ezekiel and Ruthie Ezekiel. 1889. Courtesy of the Deakin Archives, Mifflin University. |

Our online exhibition returns to the Deakin Archives as we present our next photograph from 1889. In doing so, we introduce two very important and significant individuals from the histories here chronicled. Our fourth featured tintype showcases Noah Ezekiel and his sister Ruthie Ezekiel.

Noah and Ruthie were born into slavery in Union County, South Carolina; Noah in 1855 and Ruthie in 1857. They and their older brother Zed were orphaned in early 1865 as General William T. Sherman was marching his Union army through the Carolinas. The trio fled their plantation in early February of that year and found themselves in nearby Columbia just as the city surrendered to Sherman. During the subsequent, infamous and still controversial burning of Columbia, Noah and Ruthie became separated from Zed and fearfully assumed he had perished in the mayhem and destruction. The pair were rescued by Union soldier Captain William Carr of the 10th Illinois Infantry and taken under his care. They accompanied him to Chicago where he was mustered out in July of that year.

Noah and Ruthie remained in Chicago and survived largely on their own for the next eight years, adopting their late father's name Ezekiel as their surname. Notable is that the two possessed remarkable intellects that even slavery, racism and discrimination could not suppress. Earlier in their lives they taught themselves to read with a stolen Bible, and later each became especially adept at learning skills in mathematics, mechanics and engineering.

During the summer of 1873, while working as a stagehand at Chicago's McVicker's Theatre, Noah met Magnus Maddock and his daughter Falynne. Maddock, known famously as the European stage magician the Grande Hyperion, was performing at the theater. Noah and Ruthie immediately took to respectfully deconstructing the Maddocks' carefully and artfully created illusions, and then subsequently suggesting enhancements and designs of their own. Taking no offense, father and daughter disregarded social conventions and invited the siblings into their repertoire where they stayed for the remainder of the Grande Hyperion's American tour. In October, Noah and Ruthie accompanied the Maddocks back to London where they also fell under the tutelage of Berkley Vanderzee and Geoffrey Hawkins.

The exhibited tintype features older and certainly more seasoned depictions of Noah and Ruthie Ezekiel. The photo was taken by Robert Deakin as members of the Society of the Mechanical Sun were preparing to confront Enoch Cyncad in his underground stronghold. Behind the siblings is what appears to be a Hawkins Steam Coach. This tintype is the first and perhaps only photographic record of the vehicle.